by Ed Merrison

Geoff Weaver is a man of conviction. You’d have to be to ask one of Australia’s most famous winemakers for a job before you’d so much as crushed your first grape. Or to borrow, in the early ‘80s, $100,000 at 20% interest to sink into a vineyard in a region with no vines. Or to get out and hand-plant it in your spare moments away from your full-time gig, which just happens to be making a sizeable chunk of all Australia’s wine. But Geoff – sportsman, farmer, artist – has faith in the ideal that honest toil yields eventual rewards.

That belief has been endorsed by the news that Geoff’s Sauvignon Blanc is Australia’s best, as judged by the nation’s foremost wine authority. His 2014 Ferus took out the trophy at the recent James Halliday Wine Companion Awards. He’s picked up more than his fair share of accolades in his 40-year winemaking career but that doesn’t stop Geoff greeting the latest with characteristic humility. “I’m really delighted that James has picked out our more subtle, understated styles,” he says. “I’ve always felt that as a small winemaker, you can’t be all things to all people, and you’ve got to stand for something. We do what we do; we’re not trying to match popular trends, we’re just trying to do the best thing that we can do.”

Such is his affection for the Lenswood site where the wine was grown, that it’s hard to imagine Geoff anywhere else. But there was nothing inevitable about the cricket- and footy-crazed kid’s journey into wine and the Adelaide Hills. The first seed was sown at school where he discovered an affinity for botany and geology, and struck up a fateful, lifelong friendship with Brian Croser. The two of them went on to study agricultural science together, but Geoff finished the course with no clear idea what to do next. His curiosity was piqued on visits to McLaren Vale to see his buddy Croser, who’d landed a job at Hardys. His football coach also worked in wine and helped Geoff pen speculative job applications to luminaries such a Karl Seppelt, Colin Gramp and Max Schubert. He recalls a spur-of-the-moment decision to take a post-footy drive to the home of Penfolds. “It was 5 o’clock on a Saturday afternoon and I just parked and got out and was having a look around when this guy walked out the main door. I thought I’d better come clean, so I went over and said g’day and we just got talking and I said, ‘As a matter of fact I’ve just written to your company about a job’.” It turns out it was Schubert himself who’d walked out the door, and he offered Geoff a job there and then. “I was this kid with stars in his eyes driving down the main drive at Magill thinking, ‘I’ve got a job in the wine business!’” He ended up turning down the creator of Grange to take a job with Orlando (now Pernod Ricard Winemakers), who offered to pay him $30 a week and send him to Roseworthy Agricultural College to get his winemaking qualification. For a kid with no money and a beat-up, windscreenless Vauxhall Viva, the offer was too good to pass up.

He ended up turning down the creator of Grange to take a job with Orlando (now Pernod Ricard Winemakers), who offered to pay him $30 a week and send him to Roseworthy Agricultural College to get his winemaking qualification. For a kid with no money and a beat-up, windscreenless Vauxhall Viva, the offer was too good to pass up.

He learned a great deal under the tutelage of Mark Tummel and Gunther Prass but was persuaded to join Croser at Hardys in 1975, only for his mate to move on within months. “I thought, ‘Shit. I’m a young kid and I really don’t know my way around but I’m in charge of 3% of Australia’s wines here’,” he says. Geoff being Geoff, he dealt with it. Initially in charge of the Hardys whites, taking in brands such as Siegersdorf and Old Castle Riesling, he worked his way up to the position of chief winemaker in 1987.

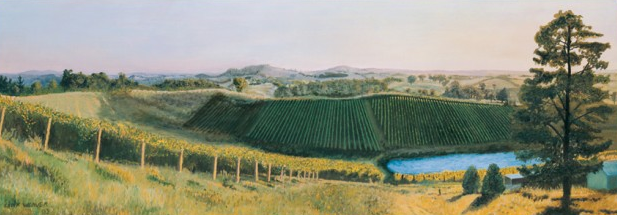

That, though, was five years after he’d passed a more cherished milestone. He and his winemaking pals had long been pooling their pennies to taste the world’s classic wines, delving into their detail, striving to unlock the DNA of their greatness. Australian whites, in particular, looked clumsy, alcoholic and short on aromatic finesse in comparison. Geoff became convinced that the key was a warm site in a cool region, which led him to the hitherto unplanted Adelaide Hills. Days were spent scouring the rolling landscape for the right spot, thermometer dangling out of the car window. “The deal was that we felt we could push back the frontiers of Australian winemaking. At that time we were dominated by the traditional areas of Barossa, McLaren Vale – Yarra was pretty new, Tasmania was pretty much unheard of and Margaret River was just really starting, and we felt the Adelaide Hills could do a lot.” And there it was: the rundown, 70-acre hobby farm that was his destiny. “My dream had always been to be a small winemaker and in 1982 we bought land at Lenswood. We had no money – of course you don’t have money – and the interest rates were 20%. I had two partners and we cobbled together $10,000 between us to buy a $110,000 property.”

Even then, it almost didn’t happen. The bank almost pulled the plug. Others caught wind of the winemaker sniffing round for vineyard land and threatened to buy it from under them. But Geoff, whose guileless Aussie vernacular is punctuated with surprising literary allusions, was resolute. “I’d been reading Émile Zola’s The Earth and I realised those French guys, they fight tooth and nail to do stuff, and I realised it was a life-changing moment. We were out on a limb but I knew we had to do it.”

That’s when the hard work began. Hardys was going full throttle, and weekends were given over entirely to his own patch – at the expense of his beloved footy, cricket and wife Judy, who that same year gave birth to their first child, Alexandra. With no machinery and no money to buy any, this meant begging, borrowing and burrowing away with his bare hands – as well as those of his father, Henry (pictured below), who spent thousands of hours at his side. Playing over and over in Geoff’s head, as he traipsed up and down the furrows, was an adage he’d read on a Vincent van Gogh sketch of a man pulling a harrow: “If one has no horse, one is one’s own horse”.

Geoff and Judy’s mettle was to be tested again in the most dramatic of ways, long before a drop of wine had been made. The Ash Wednesday bushfires of February 1983 ripped through the region and destroyed all they’d done. Again, though, Geoff was sanguine. “It’s like playing footy. You get a whack, you’ve got two choices. Do you get up or do you capitulate?” he says. “Well, I thought, we’re not capitulating. We didn’t. I said, ‘It’ll be a Garden of Eden one day; it’ll be beautiful’.”

And so it has proved. “It felt really right from day one. I’ve never regretted where we’ve chosen. We’ve been very fortunate, we’ve got beautiful soils – sandy loam over bright-coloured orange/ochre clays – and enough water in the soil, but with good water and air drainage.” The roots go deep in search of moisture, to which Geoff attributes the intensity and vitality of his wines. He also sees the naturally low pH of the wines as contributing that savoury, stony character that some are moved to call minerality. He capped the plantings at 35 acres under vine, from which Geoff produces Riesling, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir plus two iterations of Sauvignon Blanc – one reared in nothing but stainless steel, and the wild-fermented, lees-stirred, old oak-aged Ferus. The dappled light and low yields of this dry-grown site produce exactly the kind of wines he’s looking for. “What I want with the Sauvignon Blanc is that juicy, zingy quality; that supple, almost sweet middle palate coupled with that gentle, dry, acid austerity – but not aggressiveness,” says Geoff. He appears to have hit the mark, with Halliday declaring him “a master of his art”.

It comes as no surprise that Geoff highlights the invaluable support of friends along the way. Chief among them are old pal Brian Croser, and Martin Shaw, who’ve allowed him to compose his wines under their roofs at Petaluma, Shaw + Smith and, nowadays, Tapanappa. And all this time, he and Judy have battled away to pay down the debt. “If there’s a tortoise and hare story, we’re definitely the tortoise. We’ve just plodded along trying to make the best wines we can.”

These days Adelaide Hills is well and truly on the map for exceptional cool-climate wines. Shaw + Smith have enjoyed great success and there are those like Tim Knappstein and Stephen Henschke who, without conferring, had the same idea at roughly the same time as Geoff, the three of them ending up practically next door to one another. And then there’s the boundary-pushing new-wave producers such as Gentle Folk and Commune of Buttons.

Quick though he is to point to the prowess of others, his thoughts are often confined to what’s right in front of him. He loves to paint and ponder the joys of life and family in the solitude of his Lenswood home. “It’s just so grand to be there. It’s beautiful to be engaged in what’s essentially an agricultural, horticultural and artistic pursuit in this glorious countryside,” he says. Often at day’s end he simply sits atop the hill and takes it all in. “How blessed are we to live in this great country and to have the opportunity to do these things?” he wonders. “It’s just fantastic.”